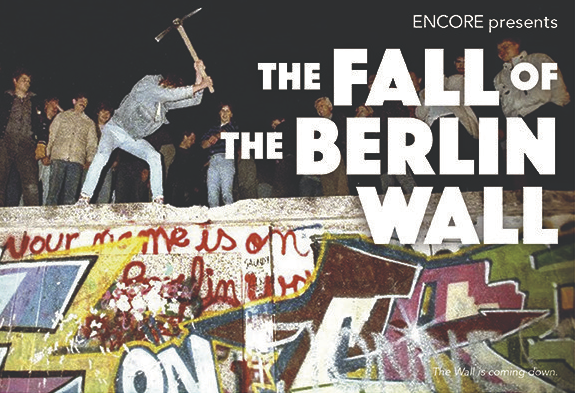

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the reunification of the two Germanys. That event came about as a consequence of the East German people’s unexpectedly bringing about the fall of the Berlin Wall. ENCORE, the Northwest Coast’s senior education association, had planned to commemorate this event in a special public program on May 17. However, the program fell victim to the coronavirus.

Our organization had invited Mr. and Mrs. Manfred Riedel who were to present “The Fall of the Berlin Wall” here in Astoria. The Riedels lived behind the Iron Curtain all their lives. They were eye witnesses and participants in one of the greatest political events in recent history. In 1982 Manfred Riedel and his wife, Petra, were offered the opportunity to visit Cuba. For people behind the Iron Curtain, the German Democratic Republic in this case, this was a once in a lifetime opportunity. As could be expected, the prospect of such a trip filled them with eager anticipation. Since East Germans were basically denied travel outside of East Bloc countries, this opportunity presented something to live for. However, to secure the actual permission to go on this trip required final clearance from local police, the political commissar at Riedel’s employer’s office and East Germany’s secret police, the Stasi. In order to finance the trip, Riedel had cashed in his life insurance policy. The final approval arrived 10 days before the scheduled departure of the flight to Havana. While Riedel was in Havana, he wrote many post cards including one each to his father and brother-in-law, who both lived in West Germany.

The Riedels were middle-aged when the fabric of East German society began to crumple. A restive citizenry, no longer denied information from Western television and radio, wanted choice and real freedom. Although very cautiously, East Germans demanded the right to go visit their relatives in the West. They remembered well the blood bath of June 17, 1953, when Soviet tanks reestablished the supremacy of the Communist government. The new leader in the Kremlin, Mikhail Gorbachev however, had made clear, that each member country of the East Bloc was responsible for its own internal affairs.

As East Germans tried desperately to escape from the oppressive atmosphere of their country -- some heading to Hungary, some to Czechoslovakia in order to reach West Germany via Austria, and the antigovernment demonstrations at home gained strength, their government prepared to imprison thousands of its citizens – in desperation the communist party leadership even replaced the head of the regime. But it was too late. A misstep by their top leadership unexpectedly opened the Berlin Wall in the evening of November 9, 1989. The whole world, including the American CIA, was as surprised as Manfred and Petra Riedel that the symbol of the Cold War, the Berlin Wall, came down that evening.

After the reunification of Germany in 1990, citizens of the former German Democratic Republic could apply to the government to get their secret police file. Mr. Riedel’s file consisted of 26 handwritten pages plus photo copies of the post cards he had written to his father and brother-in-law from Cuba. Surprise? Not really. Spying by government authorities and common citizens upon each other was common and pervasive. (The twice Olympic gold medalist figure skater Katarina Witt had 1354 pages in her Stasi file.) Having traveled behind the Iron Curtain on several occasions and having been spied upon repeatedly, the present author submitted a formal request for his Stasi file on July 13, 2019.

In order to provide my lectures on recent German History with first-hand reports, I had contacted two parties in former East Germany with the request for their recollections of experiences, feelings, anxieties and expectations during the run-up to the fall of the Berlin Wall. Both lived through those times as middle-aged adults, and both provided me with detailed personal observations and thoughts during those heady days. Common citizens of the East frequently did not know what was going on at the secretive higher levels of their government. But even functionaries at the top were not always sure. The best example for the latter is the inadvertent opening of the Berlin Wall when it was not scheduled to open. Here is how. While the government press secretary and party boss of East Berlin, Günter Schabowski, was hurrying to a press conference that was attended by foreign correspondents, he was handed several documents. During the question session, an Italian correspondent asked whether it was true that the GDR government was considering dropping some of the more draconian preconditions for persons who wanted to visit relatives in the West. Schabowski confirmed that. The next questioner asked when that would take effect. Schabowski shuffled through the papers he was given hastily but couldn’t find what he was looking for. He finally allowed that to his knowledge it was to happen “immediately, without delay.” This news went out into the world like wildfire. Within an hour, throngs of people appeared at the Wall, both from the East and the West. Local border troop commanders contacted their superiors all the way up to their commanding general. He had no information. He raced to the Wall at the iconic Brandenburg Gate, where several thousand East Germans had assembled. Knowing that his troops would not stand a chance if they tried to keep the people from pressing through the hastily opened crossing point, the general ordered his troops to stand down. By midnight of November 9, thousands of citizens had crossed in both directions. (Matter of fact, inside of one month, 33,000 Easterners had moved to the West.)

The new directive Schabowski was unable to find at the press conference was actually scheduled to take effect the next day. Although with reduced preconditions for applicants, the crossings were to be strictly controlled. But it was too late. People were flooding across the border. It was the coup de grace to the arch-communist government of the GDR. Without a single shot fired, the people were victorious.

My other contact from the former GDR had been my nephew, Steffen Gläser. Like his father and mother, Steffen was basically apolitical. His hometown, a small farming village of fewer than 1000 people, offered little in the way of entertainment to local youth. During the summers, the local outdoor swimming pool was the meeting place of young people. The place was badly in need of repairs, but there was no money for it. Steffen became a leader in the group of teenagers who organized voluntary repair activities. Steffen thus came to the attention of the local mayor who suggested that Steffen stand for election to the town council. Thinking that town council was apolitical enough, Steffen allowed his name to appear on the ballot and – at age 18 -- was elected.

Like all young men Steffen was drafted into the East German Peoples’ Army. In 1973 he had reported to the assigned military installation, and shortly after arriving was contacted by a person who suggested that Steffen could be released from military service if he would provide certain information to the Stasi. Steffen reported: “One of the Stasi officers urged me to be of service in the ‘stabilization and security’ of our country against the evil counterrevolutionaries” – meaning Westerners.

Although not identified during the initial contact, one of the targets of this reporting focused on me, his American uncle. Since Steffen did not categorically refuse to cooperate, he was released from compulsory military duty. Several weeks later, the same Stasi officer contacted Steffen again. This time, my nephew flat-out refused to turn informer. And, although threatened with repercussions, surprisingly was left alone.

If the hook did not hold in the teenage son, his father would become the next target. Shortly after, father Gläser was visited by two men in trench coats. The secret police agents wanted the father to report on me, the same American visitor, who was known to arrive soon to visit his terminally ill mother in the summer of 1974. Father Gläser likewise rebuffed their attempts. As it turned out, both father and son were politically fairly untouchable because Steffen had constructed a powerful TV receiver station for a high-ranking regional political leader so that this functionary could (illegally!) receive West German TV. Matter of fact, my brother-in-law advised me in the late 1970s to contact him immediately if I were accosted by East German authorities. He had an influential acquaintance.

The secret police had attempted to set their hooks in my nephew and brother-in-law but didn’t get a good bite. Ultimately, the repressive regime’s hooks failed on most East German citizens. With the fall of the Berlin Wall the people brought about the disappearance of the entire German Democratic Republic.